SITRA’s new study: Circular Innovation and Ecodesign in the Textiles Sector

The textiles and apparel industry has a high environmental footprint, and the current production and distribution system is almost completely linear. Fast fashion – speed and volume – has become the norm over the last couple of decades. Moreover, textile production and consumption are expected to triple by 2050. This, in turn, would significantly increase the environmental strains generated by the industry.

Published by The Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra, this study seeks to better understand the opportunities and challenges of an inclusive circular economy transition in the textiles and apparel industry. It takes a deep dive into three developing countries that rely heavily on the EU market for textiles and apparel exports: Bangladesh, Vietnam and Sri Lanka.

Specifically, the study focuses on questions such as:

- What are the implications of the EU’s circular apparel and textiles policy proposals on developing countries exporting textiles and/or apparel products to the EU?

- How can the European Commission’s proposal for the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products (ESPR) be designed so that that it minimises market access implications for developing countries?

- And how can regional trade agreements (RTAs) be leveraged to address circular economy challenges and opportunities in developing countries exporting textiles and/or apparel products to the EU?

The urgency of a circular apparel industry

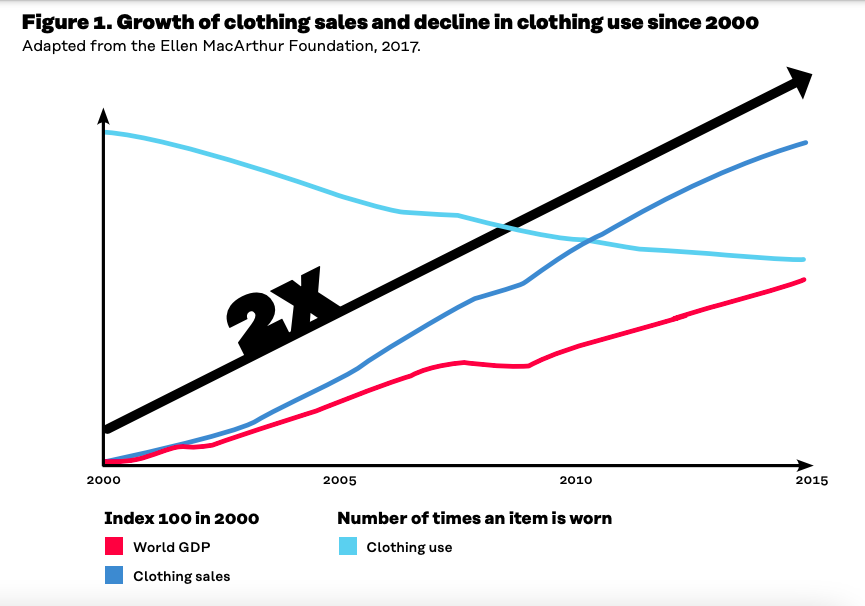

According to the study, over the past 15 years, apparel sales have almost doubled, reflecting the demand from a growing global middle-class population as well as an increase in per capita sales in advanced economies (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017: 18). As illustrated in Figure 1 below, coupled with the increase in clothing sales is a significant decline in clothing use (UNEP, 2020). This is driven by the “fast fashion” phenomenon, which, through quicker turnarounds of new styles, poorer-quality garments and lower prices, is turning apparel into a single-use commodity. The rapid growth of textiles has largely been enabled by synthetic fibres, produced from oils, which over the past 20 years have grown from under 20% of global fibre production to over 60% of production in 2018 (Textile Exchange, 2018, cited in UNEP, 2020).

Figure 1 / Sitra

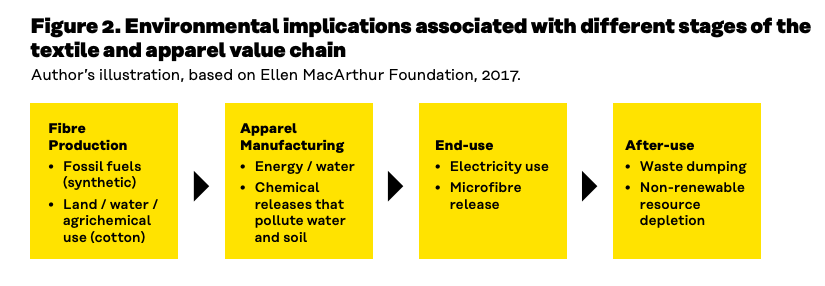

The current system of textile and apparel production and distribution is almost entirely linear. Non-renewable resources, such as oil, fertilisers and chemicals, are extracted and manufactured to produce clothes, which, when discarded, tend to end up in landfills or are incinerated. This process puts pressure on natural resources, degrades ecosystems and generates large amounts of pollution and waste.

It is estimated that, when considering the full life cycle of clothing, the textile and apparel industry generates as much as 3.3 billion tonnes annually in CO2 emissions (HoC, 2019). Put in context, this value exceeds the combined emissions of all international flights and maritime shipping annually.

Figure 2 / Sitra

Value chains in the textiles sector are notably international. The EU and other developed countries are major consumers and importers, while a significant part of the large-scale production takes place in developing countries. The EU is the largest importer of clothing worldwide, importing over half its textiles and apparel. 44.9% of all clothing imports to the EU, measured in terms of value, came from developing countries. The successful uptake of new circularity requirements in producer countries will be key to ensuring both global and local environmental benefits as well as opening up valuable new markets and creating jobs. This will not happen by default, however, but requires strategic planning and policy coherence

Key findings

Initiated by Sitra and written by Colette van der Ven, a trade lawyer and sustainability specialist, this study provides analysis and vision for how trade arrangements with the EU could be leveraged to support the transition, offering producer countries – on the example of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Vietnam – targeted technical support and investment while minimising the risk of new trade barriers.

Key take-aways include:

- Private vs public sector: Most of the circular textile initiatives in the three countries studied are spearheaded by the private sector, often supported by donor-led initiatives. In each of the three countries studied, voluntary sustainability standards play an important role. This is in part because many companies in the countries studied are foreign owned, with brands pushing for their operations to become more environmentally sustainable. There is, however, a notable absence of government involvement in establishing textile waste-recycling incentives. For effective post-industrial waste management, it would be important for governments to establish adequate regulatory frameworks. Failure to do so would, in a best-case scenario, lead to a bifurcation where foreign-owned companies supplying the export market would adopt circularity principles, while factories supplying the domestic or regional market would continue to engage in linear, and environmentally harmful, practices

- Another observation is that circular economy initiatives adopted in the countries studied seek to reduce the environmental footprint of the product. They do not, however, focus on making the product itself more circular, through enhancing reusability and recyclability in the way the product is designed. This is important for three key reasons: a) most of the added value will take place in upstream design activities – not waste-management activities; b) 80% of the environmental impacts of a product are determined at the design phase; and c) because the ESPR focuses on the circular characteristics of the product itself, not the production process.

Download the study “Circular Innovation and Ecodesign in the Textiles Sector” here.

//

News source & images: Sitra.fi